The remains of a large-scale First Nations fishery at low tide.

England’s monarchs were sacrificing to Woden and persecuting Christian missionaries when First Nations managed a vast, highly-productive, industrial-scale fish harvesting complex in the estuary of the Courtenay River.

At first, the elaborate arrangement of 300 ingenious traps on the sandy flats of the river mouth harvested herring, which still mass to spawn off the east coast of Vancouver Island every March.

But 700 years ago, perhaps in response to climate change, the technology was altered to exploit pink, chum, coho, chinook and possibly sockeye salmon.

Highly coordinated traps equal in technological sophistication to contemporary commercial fishing traps, enabled the operators to regulate escapement of spawning stocks and maintain abundance, precisely the sustainable resource management model we strive for today.

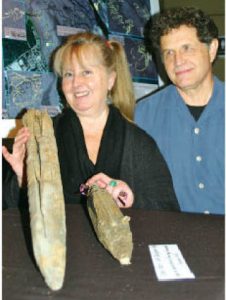

We know all this because Nancy Greene, a mature student at Malaspina College (it has since become Vancouver Island University), took a break from dreary course work surveying archaeological research in the Comox Valley one grey day in 2002.

Greene decided to visit a nearby site once excavated by Katherine Capes, a legendary early female archaeologist she had just been reading about.

The tide was extraordinarily low. Greene and her husband, David McGee, strolled there among the beach pools and seaweed of the exposed flats.

Greene noticed peculiar knobs of driftwood protruding from the sand. She stooped to examine one. It looked like the work of human hands. At that moment, she had an epiphany.

“I saw stakes everywhere … just everywhere I looked,” Greene told me not long after. “The more I saw, the more I realized that this was vast. I didn’t even know what to call them. I didn’t know they were called alignments. But I realized its potential importance as an archaeological site.”

Greene was looking at what may be the largest prehistoric archaeological feature on the Northwest Coast.

From that moment, Greene knew what her college project would be. She would map part of the site, locate each stake, record its position and, if possible, determine its age.

She had no inkling of the scale of her undertaking. It would take Greene, McGee and Roderick Heitzmann — a retired Parks Canada archaeologist who later came on board to advise on the arcane technical rules for writing up their findings as a scientific paper — a full decade. From 2003 to 2013, using precision surveying equipment, Greene and McGee mapped and recorded 13,000 of the 200,000 artifacts she now estimates the site holds.

It was exhaustive and exhausting work. To complete mapping, Greene recruited volunteers for a task that demanded meticulous detail and accuracy, but was hampered because the whole site is submerged for much of each day.

It was exhaustive and exhausting work. To complete mapping, Greene recruited volunteers for a task that demanded meticulous detail and accuracy, but was hampered because the whole site is submerged for much of each day.

Her husband signed on. Mike Trask, an amateur paleontologist famous for discovering the West Coast’s first fossil elasmosaur (a long-necked, fish-eating reptile from the Cretaceous period) stepped up. Steve Mitchell, a professional surveyor, volunteered expertise and specialized equipment.

Next came the matter of paying for expensive carbon-dating tests to determine the age of organic material by measuring its radioactive decay.

Greene’s community also stepped up. Comox Valley Project Watershed Society provided funds. Comox Valley Regional District chipped in. The municipalities of Comox, Courtenay and Cumberland, the federal Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, the K’omoks First Nation, Hamatla Treaty Society, which includes the Wewaikay of Cape Mudge, the Weiweikum of Campbell River, the Kwiaka, the Tlowitsis and the K’omoks, all helped.

So did 27 individual and business donors, organized by then-Comox Valley Regional District director Jim Gillis into the “Stick in the Mud Club.” His idea was to mobilize a cross-section of the community as a non-traditional way of funding important local archaeological research.

Greene, McGee and Heitzmann have just published their research in the prestigious Canadian Journal of Archaeology. It documents a major discovery in Canada’s prehistoric landscape. Their paper charts with astonishing detail the immensity of the site, from defensive fortifications to huge refuse middens stretching three kilometres along adjacent shorelines and, of course, the huge geometric designs of curves, angles and parallels of the traps themselves.

Perhaps most fascinating among the many astonishing findings is how the technology — it was designed to capture fish at every stage of the tidal cycle — evolved over at least 1,400 years of continuous use as its operators adapted it to exploit climate-driven changes in the fishery.

“We have taken the research to a whole new level, which allowed us to critically analyze the data and draw some significant conclusions about this immense aboriginal fishery,” Greene says. “Our research is the first of its kind to study in detail these previously unknown marine fishing practices and it is the first indication of a long-term, sustainable, possibly industrial-scale aboriginal fishery on the Northwest Coast.”

Call it a triumph of citizen science.

shume@islandnet.com

View the oriiginal article at – http://www.vancouversun.com/health/stephen+hume+archeology+student+publishes+paper+ancient+industrial+scale+first+nations+fishery/11677919/story.html